I was 12 years old when the Chernobyl disaster happened and I remember being quite aware of the dangers of nuclear events - I'd learned about Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the enduring impact of the atomic bomb. Chernobyl was something else. It was a catastrophic and unprecedented disaster; we didn’t immediately know what the lasting effect would be but we knew that they were in trouble.

It was little surprise then when the years passed and we learned that Pripyat and surrounding areas had become ghost towns, areas that would be unfit for human habitation for another 10,000 years (or so estimates go).

But people do live there. They cut through fences and snuck past military patrols to resettle in their homes or to make new homes, surrounded only by the ghosts of the tens of thousands of people that once lived in those towns and the ever-present spectre of radiation.

Svetlana Alexievitch, Belarusian investigative journalist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2015, spoke to those people and indeed, to people from all walks of life who were effected by Chernobyl. She spoke to widows and survivors, liquidators, contractors and military reservists who were called to Chernobyl in the days after the disaster. She spoke to families who had been evacuated from Pripyat and surrounding areas, to those who returned and to those who fled the war in Tajikistan to settle there because they had nowhere else to go.

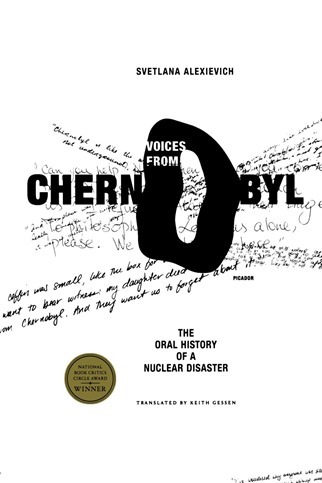

Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster reads like a dystopian novel, or perhaps a post-apocalyptic survival story. First published in Russian in 1997 and expertly translated by Keith Gessen, Voices from Chernobyl is the fruit of hundreds of interviews that Alexievitch obtained over a three year period. It is an incredible and page-turning volume with accounts as fascinating as they are obscene.

It’s difficult to put into words how much of an impact this book has on the reader and any attempt will be nowhere near as eloquent as the accounts themselves. The lack of understanding of the dangers that people faced, coupled with a massive campaign of disinformation is perhaps most notable. In the aftermath of Chernobyl, they sent cranes from East Germany and robots intended for the Russian Mars exploration. Even robots from Japan made it to the site but the radiation interfered with all their workings and so they resorted to sending human beings in rubber suits instead.

There were 340,000 personnel despatched to Chernobyl but those working on the roof of the reactor got it the worst. They were wearing lead vests but the radiation came through their boots.

And then, throughout the book is the ever-present reminder that the Chernobyl disaster happened to a population less than 50 years after the Second World War.

Gulag, Auschwitz, Chernobyl. One generation saw it all.

What impressed me the most is that many of these people survived the Leningrad blockade only to suffer devastation again in Chernobyl. They spoke of the terrible winters during the blockade where people froze to death on the streets and one man mentioned, perhaps in jest, burning his belt so that the smell could stay his hunger.

Voices of Chernobyl is a study in the various shades of trauma. Some interviewees expressed that they couldn’t talk about the blockade, it was too traumatic, but Chernobyl they could talk about. Despite the catastrophic loss of life and livelihood, the events of Chernobyl still felt less traumatic to many of them than the blockade.

I cannot recommend Voices from Chernobyl enough and was so impressed that I have ordered Alexievitch’s latest book Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets which was shortlisted for the 2016 Bailie Gifford prize for non-fiction.

No comments

Post a Comment